Plastic awareness is now a core literacy for young Australians. Students encounter plastic in lunch boxes, drink bottles, uniforms, stationery and sport equipment. They also see headlines about ocean waste, landfill pressure and microplastics in food and water. Classrooms offer the most reliable setting to separate fact from myth. Good teaching gives students the language, the science and the daily habits that lower personal exposure and household waste. It also builds informed demand for better packaging, including biodegradable HDPE and LDPE that do not leave microplastic residue at end of life.

Education systems already teach resource use, health and civic responsibility. Plastic awareness aligns with these goals. It links chemistry to real products, biology to human exposure, geography to waste systems and economics to product design. It fits project based learning and supports school wide sustainability programs. Most important, it equips students to make safer everyday choices and to ask better questions of brands and policymakers.

What plastic awareness means for student health and science literacy.

The science around plastic exposure is evolving. Studies summarised by the World Health Organization explain that plastic particles are now found in water, food and indoor dust. Recent public reports from Columbia University and UCLA Health show very high particle counts in bottled water, with most particles in the nano range. Clinical literature has detected plastic fragments in human arterial plaques. While research continues, the consistent message is that reducing unnecessary exposure is a sensible health choice. Teaching these facts with care and clarity helps students understand why material choices matter.

Plastic awareness also improves science literacy. Students learn how analysts count very small particles with spectroscopy. They learn how lab studies differ from population health studies. They see how regulators and retailers translate evidence into policy and procurement. They learn to read labels closely and to look for independent certification rather than slogans.

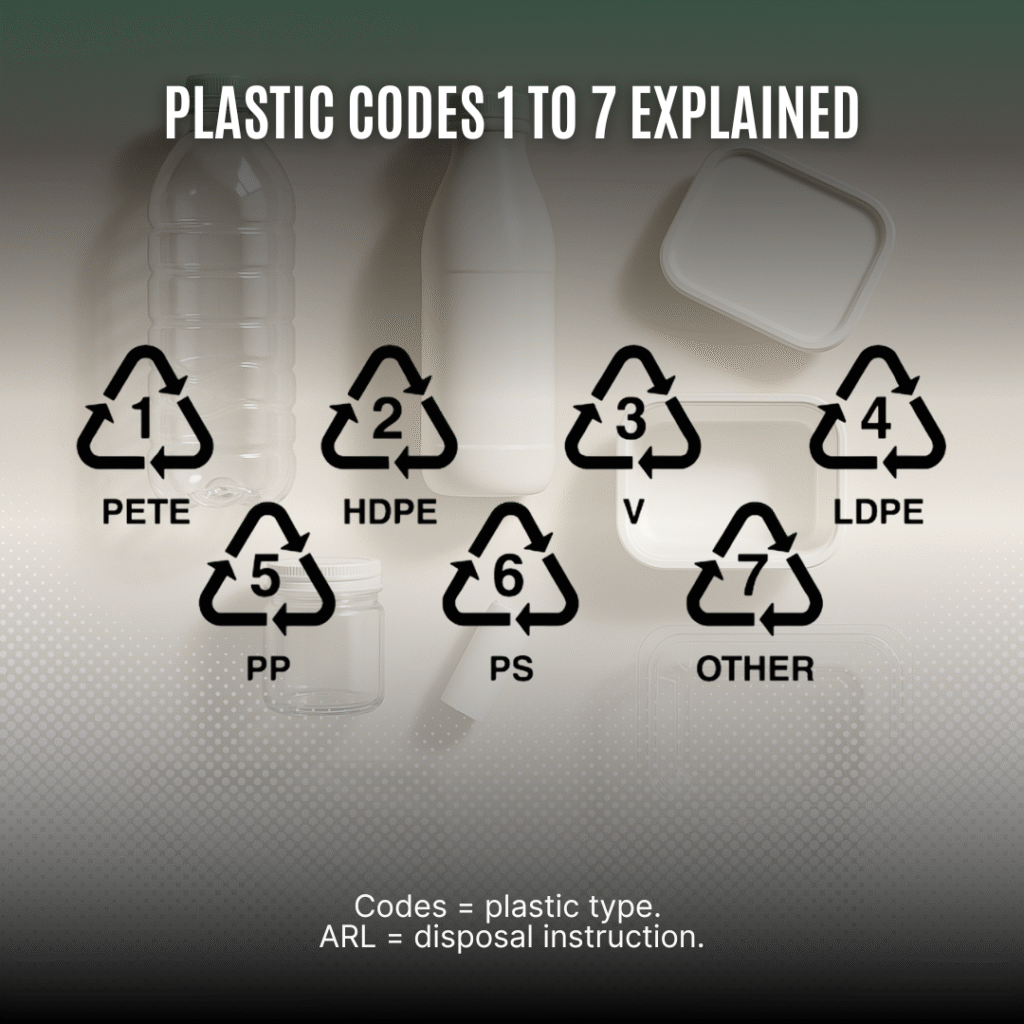

The recycling codes explained for Australian classrooms.

The plastic identification numbers from one to seven help students recognise families of polymers. These numbers appear inside a triangle of arrows on many items. The codes describe the type of plastic, not a guarantee that a local council can recycle it. Explaining this difference prevents disappointment and builds realistic behaviour.

1. PET, polyethylene terephthalate.

Often used for soft drink and water bottles. Light and clear. Recycled in many councils, yet recovery rates remain limited. PET can shed small particles during use and storage.

2. HDPE, high density polyethylene.

Used for milk bottles, shampoo bottles and some food containers. More widely recycled. Biodegradable versions of HDPE exist and are useful when real world end of life conditions mean items will enter landfill.

3. PVC, polyvinyl chloride.

Seen in some food wraps, blister packs and piping. Recycling options are limited for consumer items. Contains chlorine and often additives, which raises disposal and health concerns.

4. LDPE, low density polyethylene.

Used for soft plastics such as bread bags and some squeeze bottles. Kerbside recycling is limited. Store drop off programs exist in some areas, but national coverage is inconsistent. Biodegradable LDPE is a relevant alternative for many packaging uses.

5 PP, polypropylene.

Used for yoghurt tubs, take away containers and many caps. Recycling access is improving, yet food contamination commonly diverts items to landfill.

6. PS, polystyrene including expanded forms.

Used for disposable cutlery, foam trays and protective packaging. Kerbside recycling is rare. Many states restrict single use items made from this material.

7. Other.

A catch all category that can include polycarbonate, bioplastics and mixed materials. Recycling is uncommon. End of life behaviour varies widely, so products in this category require careful scrutiny.

Teachers can reinforce that a number inside a triangle does not equal easy recycling. Local access depends on council systems, contamination rates and market demand for recovered materials. Students should always check their council guidelines and use the correct bins at school and at home. Planet Ark’s Recycling Near You is a practical tool for this step.

From codes to choices. How to teach safer material selection.

Once students learn the codes, the next step is choosing better options for the situations they control. Clear rules of thumb help.

Prefer durable and washable items over single use.

Choose certified biodegradable HDPE or LDPE where products will realistically enter landfill after use.

Avoid products made from PVC, polystyrene and mixed plastics for food contact and short life packaging.

Look for independent certification rather than vague eco labels.

Treat refill systems and bottle re use as complementary to biodegradable packaging, not as rivals.

These rules give families and schools practical guidance that reduces waste and reduces exposure. They also align with current state bans on certain single use plastics and with retailer goals to reduce problem polymers.

Classroom activities that build plastic awareness.

Weigh the week.

Students bring a week of clean household plastic packaging to class. They sort items by code, weigh each category and chart the results. Classes then identify which categories have poor local recycling access and plan substitution ideas.

Label literacy.

Teams collect examples of environmental claims from supermarket items. Students check each claim against ACCC guidance for green claims and identify which statements need proof, which are acceptable and which are unclear.

Water bottle test plan.

Older students design a fair test to compare bottles stored in cool shade and in a hot car. They cannot measure tiny particles in class, but they can design the protocol, define variables and write a plan that a laboratory could execute.

Lunch without legacy.

Students redesign a typical school lunch pack to remove single use plastics. They document the cost, the time to prepare and how the materials are disposed of. They repeat the exercise for a school sports event.

Debate with evidence.

One team argues for recycling only. The other team argues for biodegradable materials where recycling fails. Students must use public sources and explain the limits of each approach. The class then drafts a balanced policy for the school canteen.

How biodegradable HDPE and LDPE fit school procurement.

Schools buy large amounts of consumables. Bin liners, canteen containers, catering wraps and event drink bottles are frequent purchases. When items are likely to enter landfill, certified biodegradable HDPE and LDPE reduce long term residues and remove the risk of microplastic release as the item breaks down. These materials behave like conventional polymers in use, then undergo controlled depolymerisation in landfill conditions. That means no special collection or industrial composting is required, a key advantage for regional schools and for event waste.

Procurement officers can request independent test reports and certification marks. They can also ask suppliers for plain language statements that confirm no microplastic residue, no methane release and no toxic leachate during breakdown. This documentation supports school sustainability reports and aligns with council waste strategies.

Addressing common myths in student friendly language.

Myth 1. The triangle symbol means a product is recyclable everywhere.

Reality. The symbol identifies material type. Local recycling depends on council systems and contamination.

Myth 2. Plant based plastics are always better.

Reality. Some plant based plastics behave like conventional polymers and still fragment into microplastics. Certification and end of life testing matter more than the feedstock.

Myth 3. Reusable bottles remove all risk.

Reality. Re use is preferred, yet material choice still matters. Some plastics shed particles during heat and wear. Certified biodegradable alternatives and stainless steel reduce this risk.

Myth 4. Biodegradable means the product dissolves in nature immediately.

Reality. Quality biodegradable products are engineered to break down under defined conditions and time frames with testing to confirm no persistent residue.

Linking plastic awareness to curriculum and teacher workload.

Plastic awareness maps cleanly to Australian Curriculum learning areas. Science covers materials, ecosystems and health. Geography addresses waste systems and urban planning. Design and Technologies invites packaging redesign and life cycle thinking. English teaches persuasive writing using evidence. Mathematics supports data collection and charting during waste audits. Teachers can integrate plastic awareness projects into existing units rather than adding new workload. State departments and councils already offer lesson plans and grants for school waste projects. These should be used to reduce preparation time and to fund simple equipment such as scales, clear tubs and signage.

Measuring outcomes and communicating results.

Good programs publish clear indicators. Schools can report kilograms of single use plastic avoided per term, percentage of canteen items moved to biodegradable options, number of students who can correctly explain the codes and number of households using council guides after a parent session. Communicating these results builds community support and provides evidence for grant applications. It also gives students a sense of agency and a practical record for portfolios and award programs.

How The Eco Bottle supports education and health goals.

Many schools rely on bottled water for events and excursions. Choosing a certified biodegradable bottle that leaves no microplastic residue gives families a healthier option when re use is not practical. The Eco Bottle is designed for this role. It offers safe hydration with a proven end of life profile. In the classroom, bottles can support lessons on material science, life cycle analysis and procurement decisions. In the wider community, they reduce landfill persistence when bottles are discarded after events.

Policy and community partnerships that help schools.

Councils and state agencies can standardise signage, provide audited collection services and offer small grants for canteen transitions. Retail partners can co develop school safe product packs made from biodegradable HDPE and LDPE. Universities can mentor senior students on testing methods and data analysis. Parent groups can run information nights that explain recycling codes and local access. These partnerships reduce the load on teachers and create consistent messages across the community.

Conclusion. Education first makes plastic awareness a daily habit.

Plastic awareness taught early becomes second nature. When students learn the recycling codes, understand health risks and see credible alternatives, they make better choices at home and at school. They also influence household purchasing and community expectations. Australian classrooms are the best place to build this literacy. With clear lessons, reliable sources and practical procurement, schools can reduce exposure, reduce waste and normalise biodegradable materials where they do the most good.

Key Summary

✓ Recycling codes describe polymer families and do not guarantee local recycling.

✓ Teaching plastic awareness improves science literacy and supports safer daily choices.

✓ Certified biodegradable HDPE and LDPE reduce landfill persistence and microplastic residue.

✓ Classroom projects turn theory into practice with measurable outcomes.

✓ School procurement can shift high volume items to verified biodegradable options.

✓ Parent and council partnerships reinforce consistent messages and reduce teacher workload.

✓ Students who understand codes and health facts become credible advocates for better packaging.

References with public access

Australian Government, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. National Plastics Plan.

https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/protection/waste/plastics-and-packaging/national-plastics-plan

Planet Ark, Recycling Near You. Fun ways to teach kids about recycling and more.

https://recyclingnearyou.com.au/resources/schools

World Health Organization. Plastics and health initiative.

https://www.who.int/initiatives/plastics-and-health-initiative

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Bottled water can contain hundreds of thousands of nanoplastics. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/news/bottled-water-can-contain-hundreds-thousands-nanoplastics

UCLA Health. Truth about nanoplastics in bottled water. https://www.uclahealth.org/news/article/truth-about-nanoplastics-bottled-water

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Environmental claims and the Australian Consumer Law.

https://www.accc.gov.au/about-us/publications/a-guide-to-making-environmental-claims-for-business

CSIRO. Reducing plastic waste in India and Australia.

https://www.csiro.au/en/research/natural-environment/Circular-Economy/IND-AUS-Reduce-Plastics-Waste